Braiding Sweetgrass

Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge, and the Teachings of Plants is a book that weaves together Indigenous teachings and worldviews with scientific knowledge about plants and our natural world. The book was written by Dr. Robin Wall Kimmerer, an expert in environmental and forest biology and a member of the Potawatomi tribe. In her book, she writes a series of essays that describe the gifts and lessons plants provide. Most essays focus on a particular plant or plants, such as the Three Sisters, Cedar, or Sweetgrass, tying together scientific background to Indigenous perspectives of the plants.

One chapter I found particularly compelling focuses on the teachings of Sweetgrass. Kimmerer discusses how one of her graduate students decided to pursue a thesis about whether sweetgrass patches are made stronger through selective and sustainable harvesting, something that traditional Indigenous practices support. Several teachings relate to harvesting Sweetgrass, including not picking the first plant one finds and never picking more than half of the plants. At first the scientific community rejected this line of inquiry, but she ended up proving something that Elders had known all along. The inquiry illustrates the importance of Indigenous knowledge and the limitations of Western science in understanding the natural world.

Environmental themes run throughout the book, but become more pronounced by the end. Kimmerer challenges the perspective that plants, animals, and land are commodities, something to be owned and used. Instead, Kimmerer urges us to consider the reciprocity we should feel towards the natural world. She writes, "I fear that a world made of gifts cannot coexist with a world made of commodities" (page 374). She equates the latter worldview with what she calls Windigo thinking, being driven by unending greed and hunger.

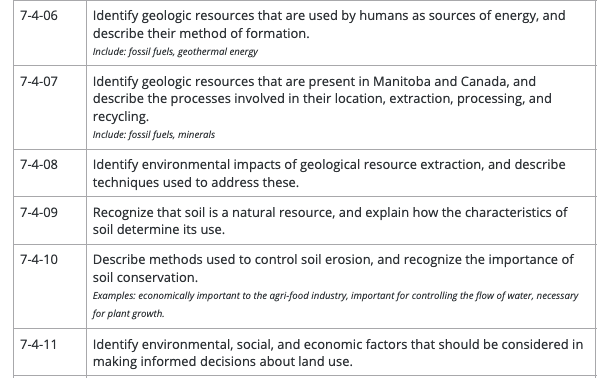

As a science teacher, this perspective challenges the curriculum I am meant to deliver. Science is often viewed as objective and fact-based, but Western-based scientific practice is guided by a particular set of values. Many outcomes I teach are based in the idea that the natural world is something people use and master. Sometimes these perspectives are couched in talk of sustainable development, which focuses on how the needs of the economy and society should be balanced with the environment.

Kimmerer quotes an Elder who says "This sustainable development sounds to me like they just want to be able to keep on taking like they always have. It's always about taking... Our first thoughts are not 'What can we take?' but 'What can we give to Mother Earth?' " (page 190). Kimmerer emphasizes that there needs to be reciprocity in how we interact with the more-than-human world. When we are given gifts from nature, we must give back in turn. She emphasizes there are many ways of doing this, whether it is "through gratitude, through ceremony, through land stewardship, science, art, and in everyday acts of practical reverence" (page 190).

After the winter break, I have been tasked with completing a two week unit on the Medicine Wheel with a small group of students, in preparation for the Medicine Wheel garden my school will be planting this spring. Discussion about the garden has so far centered on how we can use it, such as by picking berries and vegetables and using them in our home economics class. However, after reading Kimmerer's work, I am drawn to the idea of reciprocity. Our garden should not be about what we can take from it, but should emphasize what we can give back. Creating habitats and food sources for local wildlife should be part of this, but I also hope the garden will help my students have a better appreciation and more gratitude for their natural world. Going forward, I will work on emphasizing reciprocity with the natural world in my science classroom, while critically considering how the curriculum might work against this value.